Sometimes I can’t resist the urge to rescue from oblivion the forgotten casualties of WW1, who are often also those for whom the CWGC database falls short. That means I always have a waiting list of ‘war strays’ for deeper research.

But in the case of William Hamilton, one of these war strays, as I began to discover that neither the Scottish Poetry Library, an otherwise amazing haven and resource for lovers of Scottish poetry, nor the school at which he had been educated, nor the university college at which he had lectured in philosophy for four years, could find a record of him, I felt obliged to prioritise his story with a post that, I hope, is a gentle nudge that gets William a little attention from his ‘ain folk’. I have chosen to post it in this particular blog, largely because of his longing for Southern Africa, clearly expressed in his poem, The Song of an Exile.

2/Lieut. William Robert Hamilton, The Coldstream Guards

attached 4 Company Guards Machine Gun Regiment.

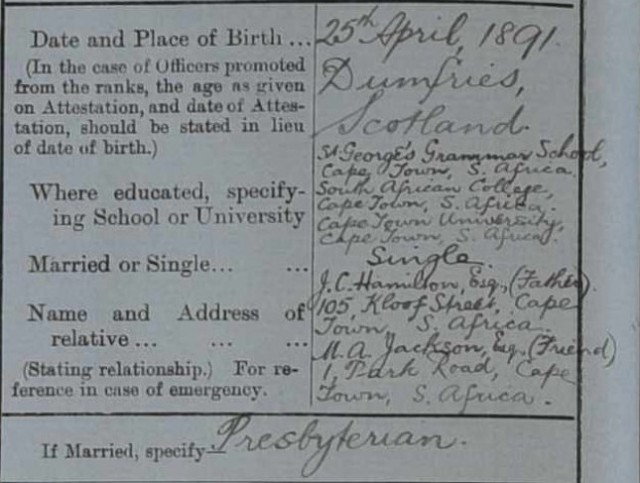

Born 25 April 1891, Dumfries, Scotland;

Killed in action, 12 October 1917,

Commemorated on the Tyne Cot Memorial.

I first came across the name of William Hamilton on an online list, Forgotten Poets of the First World War, which included his poem, The Song of an Exile. The poem seemed vaguely familiar to me so it is possible that I may have come across it in a South African anthology many years ago.

Here’s an extract from that poem—its first verse, followed by the poem’s first refrain. One can feel the yearning in the refrain.

I have seen the Cliffs of Dover

And the White Horse on the Hill;

I have walked the lanes, a rover;

I have dreamed beside the rill:

I have known the fields awaking

To the gentle touch of Spring;

The joy of morning breaking,

And the peace your twilights bring.

But I long for a sight of the pines, and the blue shadows under;

For the sweet-smelling gums, and the throbbing of African air;

For the sun and the sand, and the sound of the surf’s ceaseless thunder,

The height, and the breadth and the depth, and the nakedness there.

[Modern Poems, William Hamilton, 1917.]

William Robert Hamilton

William was born at 1 Maryville Terrace, Dumfries on 25 April 1891, the only child of John Hamilton (1858–1944), at the time a Commercial Traveller, from Keir, Dumfriesshire, and his first wife, Jane Waugh (1862–1909), a Music Teacher. In most records, she appears as Jeanie, which was then a fairly common diminutive for Jane and Jean, two popular Scottish first names. John and Jeanie were married according to the forms of the Free Church, at the bride’s residence, 86 High Street, Dumfries on 27 December 1887.

As William would turn out to be their only child, I am interrupting here, to take his story back one extra generation, in the hope that there may be descendants of his paternal or maternal grandparents who will recognise their connection with him. Following his death, there remained only William’s father and his friends to remember him, and my hope is that this post will, in due time, reach some descendants of his Scottish cousins.

William’s father and his paternal grandparents

William’s father, John, was the fourth child of Robert Hamilton (c.1818–1903) and Irving Crosbie (1824–1902), who were married on 27 June 1846 in the parish of Gorbals, Glasgow. Born at Keir Mill, John was presumably named after his Crosbie maternal grandfather and in later life, John would clarify this connection by incorporating the Crosbie/Crosby surname as a middle name. Robert Hamilton was born in Closeburn, Dumfriesshire and by the time of the birth of his son, John, was a Master Miller in Dumfries. John’s occupation, described as Commercial Traveller in 1887, and as Grain Dealer in 1891, suggest he was perhaps filling these roles on behalf of his father.

William’s mother and his maternal grandparents

William’s mother, Jeanie, was the daughter of a Minister of the Free Church of Scotland, Robert Brown Waugh (1829–1863) and Jessie Fyfe Rattray (1838–1867). Her parents were married on 18 March 1862 in Dundee and Jeanie, their first and only child, was born at Crookham, in Northumberland, where her father was then the village’s Presbyterian Minister. Jeanie was only six months old when her father died on 22 June 1863, at his parents’ home, Bengal Hill, in Durisdeer, Dryfesdale. Robert was himself the youngest child of his parents John Waugh (1775–1852) and Jane Brown (1787–1871). Jeanie was named after Jane Brown, and Jane’s surname was occasionally included as Jeanie’s middle name. Robert’s parents were both born, and brought up, in Durisdeer. The family seems to have been comfortably off—the 1851 Census has John as a Landed Proprietor and Farmer, with 170 acres at Bengal Hill, employing 11 labourers.

Like her husband, Jessie, was the youngest child in the family of David Rattray (1792–1850) a Flax Spinner and Miller and Helen Jamieson (1797–1856). She was born at Bramblebank in Rattray, Blairgowrie where, five years previously, her father, David, had moved his family from their home in Dundee. There her father built the Bramblebank Mill on the banks of the River Ericht. The mill was driven by a ‘cutting edge’ condensing engine, powered by a turbine, producing flax and tow for Fife and Forfar.

The informant at the time of Jessie Rattray’s death, on 31 January 1867, was Alexander Malcolm, who turned out to be the husband of Jessie’s sister, Jane, the sister closest in age to her. The address at which Jessie died was the Malcolms’ family home, 1 Dudhope Terrace, Dundee and was the address at which Jessie was recorded in the1861 Census, taken a year before her marriage to Robert. Following Jessie’s death from rheumatic fever just a month after Jeanie’s fourth birthday, she became an orphan, and probably retaining few memories of her mother.

I was curious to know who had cared for Jeanie between her mother’s death and her marriage to Robert. Initially I thought she might have been taken in by one of her Rattray aunts—Helen who was married to George Malcolm, the elder half-brother of Alexander, or one of her mother’s other sisters, Margaret, Elizabeth or Jane. But when next I came across Jeanie, she was recorded at Bengal Hill, in Durisdeer in the 1871 Scotland Census, living with the youngest of her Waugh aunts, Isabel, in a separate household attached to the household of another paternal aunt, Alison Waugh, and her husband, William Bell. William was farming land previously held by his father-in-law, John Waugh, but an area 20 acres fewer, and with four farm servants instead of eleven.

It was perhaps in the environment of Bengal Hill that Jeanie’s interest in music was facilitated, for in 1881 she was recorded as a Teacher of Music, living in Aberdeen, in the household of another aunt, this time Elizabeth Rattray, and her husband, William Aberdein, manager of a Jute Works there. There was a strong involvement in jute in this side of the family—the Malcolm husbands of Jeanie’s aunts, Helen and Jane, were both managers of Jute Works in Dundee. As most of the jute sent to Dundee came from Bengal, and John Waugh farmed at Bengal Hill, I have been wondering whether John Waugh could himself have been an early investor in the jute trade.

William’s story

Four years after the marriage of John Hamilton and Jeanie Brown Waugh, and three weeks before William’s birth, we find them at 1 Maryville Terrace Dumfries. Also in the household on Census Day (5 April 1891) was Jeanie’s paternal aunt, Isabel, with whom we had found Jeanie in 1871. The census has her as a boarder, living on her own means. That she was not described as a ‘Visitor’ could suggest that Isabel’s presence in the household was more than just as someone to assist with the new baby. It’s interesting that we find Isabel with her niece in the first and last Scottish censuses in which Jeanie was represented. Perhaps of all the willing aunts, Isabel was, in effect, the one most filling the role of a surrogate mother to Jeanie.

I have found no convincing entries on the available passenger lists of ships bound for Cape Town that include William’s father, his mother or William himself, so we cannot yet be sure when the family emigrated to the Cape Colony. I have not been able to find them in the 1901 census, so I am tentatively assuming that they emigrated before the Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902) and thus before the deaths of John’s parents, Irving and Robert in 1902 and 1903 respectively.

We know that William received at least some of his primary education at St George’s Grammar School, a cathedral school, at the time attached to St George’s Cathedral in Cape Town. At about the age of 12, William would have embarked on his secondary education at the South African College School, known locally as SACS. Founded in 1829, it is said to be the oldest high school in Southern Africa. In about 1874, the school added a small tertiary education facility which grew considerably over the last two decades of the 19th century, because of the growing need to provide advanced technical skills for example, for mining. By the turn of the century, that ‘arm’ of the school had gained the status of a University College, and had become quite distinct from the College Schools.

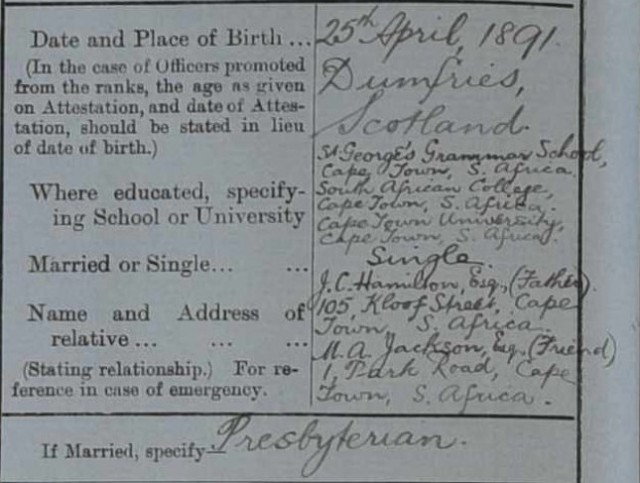

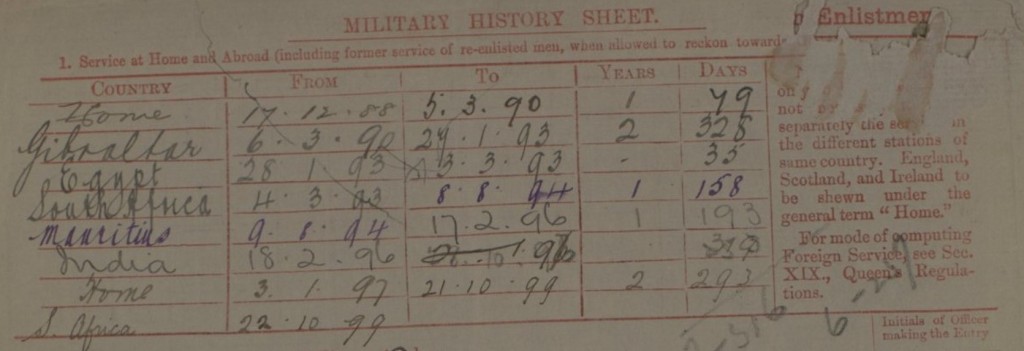

The SACS Archive turned out to have records for many Hamiltons in its admission registers for the period 1905 to 1922, but no record for William, which is not surprising because, having been born in 1891, he had probably entered the school no later than January 1903. This extract, from William’s Record of Service with the Coldstream Guards provides information about his education:

The Coldstream Guards’ list of where William had been educated.

William would have completed his education at SACS in 1908 or 1909, at around the time that his mother died. She had been suffering from cancer for six months,before her death at the Diakones Hospital, in Bree Street.

Academic life

During William’s time as a post-Matric College student, his play Moths and Fairies (1910) was published and perhaps, at some point performed. After graduating with an M.A., he was appointed as a lecturer in Philosophy and English for four years—from the start of the academic year in 1912 to the end of the academic year in November 1915.

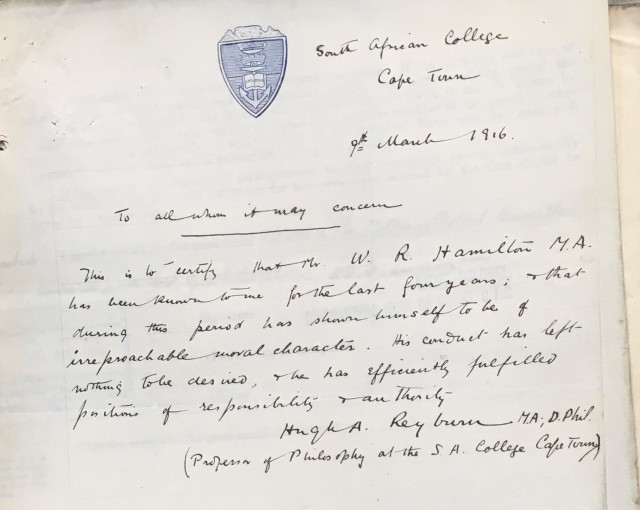

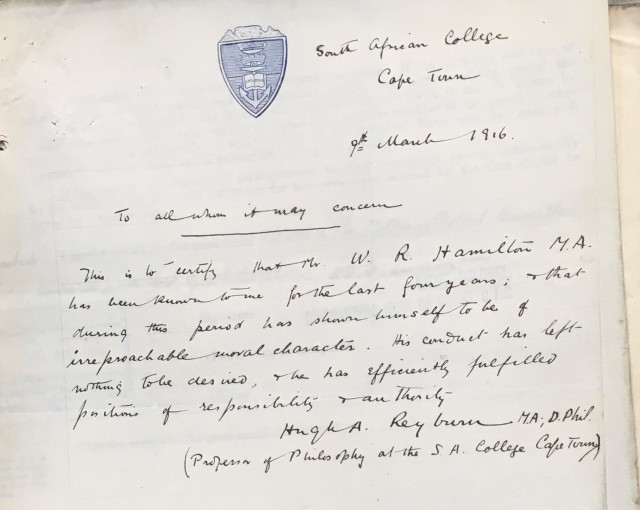

In 1912, Hugh Adam Reyburn, a native of Leven, Fife, with a doctorate in Philosophy from the University of Glasgow, was appointed Professor of Philosophy at the South African College. Besides their deep interest in philosophy, the two men had in common their relative youth—Reyburn was only five years older than William—and their Scottish roots. Within eight years of his arrival, Reyburn had developed a keen interest in psychology, promoting it and shifting his focus to it for the remainder of his academic career.

In support of William’s application for a commission, early in March 1916, Reyburn wrote that “during the period [of four years, he] has shown himself to be of irreproachable moral character. His conduct has left nothing to be desired & he has efficiently fulfilled positions of responsibility and authority.”

We know that one of his close friends was N A Jackson with whom he had shared a house at 1 Park Road, until his departure for England, This friend, along with William’s father, was listed in the records of the Coldstream Guards as a “person to be contacted in the event of an emergency”.

Off to war

There is also an earlier letter ‘in lieu of discharge’ in William’s Army Service Records, on notepaper headed ‘Judge’s Chambers, Supreme Court, Cape Town’ and signed by F G Gardiner, O[fficer] C[commanding] C Co[mpan]y Special Battalion. Dated 10 November 1915, it reveals that he had undergone some basic part-time military training ahead of his departure for Europe. Gardiner wrote:

I am very sorry that you are leaving us, but glad that the reason for your resignation is that you are going on active service, and I congratulate you on the step you are taking. I hope that the training you have had with C Coy will prove helpful to you. It is a great encouragement to those working to make the Special Battalion a success to find that we are feeding the fighting forces.

Ever protective of his equipment, Gardiner concludes, May I remind you not to forget, in the hurry of departure, to return your rifle & equipment to the Q.M.R., Drill Hall.

He was indeed in the ‘hurry of departure’. The passenger list for the Llandovery Castle establishes that the ship docked in London on 19 December 1915, though it appears William disembarked, perhaps a day earlier, in Plymouth. He is described on its passenger list as a Lecturer, aged 24, and with his country of permanent residence given as Scotland. He would have had his very last sighting of Table Mountain about two weeks earlier.

1916: William’s year in England

William wasted little time in continuing his military training. On 17 January 1916, just four weeks after his arrival, he signed up with the Inns of Court O[fficer] T[raining] C[orps] and his attestation notes that he was based near Holborn, in the household of Dr John Waugh, M.D., at Gordon Mansions, in Francis Street. Dr Waugh (1856–1937) was the son of Jeanie’s uncle, John Waugh (1824–1891) and his wife Margaret Moffat (1834–1909) and thus first cousin to William’s mother, Jeanie.

On 4 August 1916, the second anniversary of the start of the war, and following six months of training with the Inns of Court OTC, William applied for a commission in the Coldstream Guards. Having answered in the affirmative what may have been key questions—whether of pure European descent and able to ride—William was formally granted his commission on 22 August, Two days later, training specific to an officer in the Guards began, including, no doubt, extra sessions on horseback, given that he had demurred over those skills with the admission Yes…but out of practice.

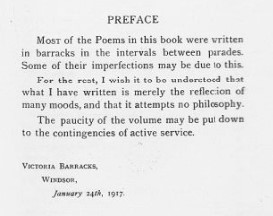

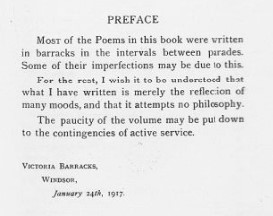

Modern Poems

The preface to his collection of poems tells us that during his military training at the Victoria Barracks in Windsor, William spent some of his free time composing the poems in that volume and that ‘most of’ the poems in the collection published in 1917 were written during his year in England.

William dedicated Modern Poems to A R Orage which suggests that he was someone whom William particularly admired. Alfred Richard Orage (1873–1934) was at the time a key figure in socialist politics and modernist culture. A former school teacher in Leeds, he had resigned in 1906 and moved to London, where he became editor of The New Age, transforming it into a broad forum for politics, as well as literature and the arts. I see, in this dedication, clues also to William’s interests and, perhaps, to his political leanings, as a young adult. His base with Dr Waugh in Holborn meant that he was within easy reach to take advantage of the cultural scene and the avant-garde ‘pushing at the boundaries’—and, indeed, to encounter influential thinkers like Orage.

Preparing for the Front

Towards the end of the year, William undertook additional training, first at Windsor, as a Gas Instructor, and then by December in Grantham, when he completed Machine Guns training. His grade for the latter, being Good, probably sealed his fate, as it resulted in his being attached thereafter to one of the Guards’ Machine Gun Battalions, in his case the 4/Machine Gun Guards Battalion. His service records show that he was hospitalised at Etaples in June 1917 for almost a month, during which he was treated for an abscess.

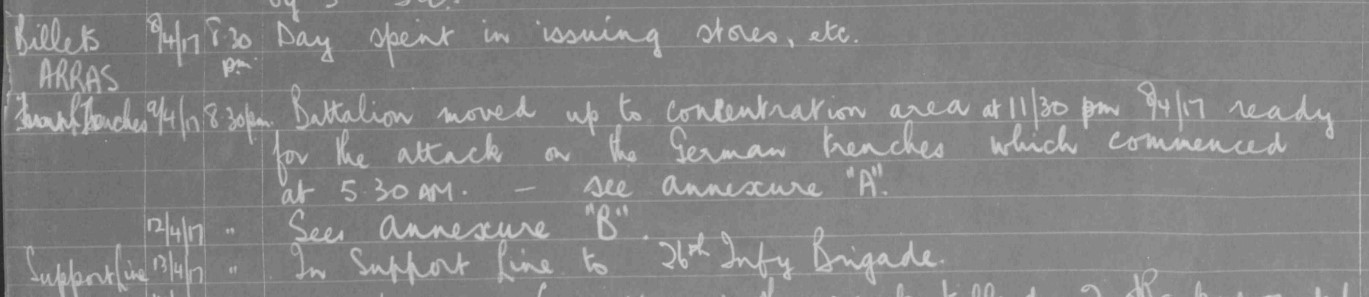

The entry in the War Diary below, from of 4th Guards Machine Gun Battalion records that William returned from leave two days before his death. Only hours after first uploading this blog post, I found William was featured by A. St John Adcock in Chapter 8 of For Remembrance: soldier poets who have fallen in the way (1920). Adcock wrote that William’s “book was not published till after he had gone to the front, and a copy of it reached him only a few days before he was killed in action there.” But since he returned to the Front from English leave less than 48 hours before his death, I think it likely that he would have received a copy while he was in England, and, one hopes, been able to forward copies to those closest to him.

10/10/17 The whole company was present in FOREST AREA. 2/Lt Hamilton returned from English leave.

The entry below for 12 October 1917 covers the action in which William lost his life in an attack on Houthulst Forest. In the course of the war, the German forces had made the forest an almost impregnable fortress, holding it until September 1918, when Belgian forces finally ‘evicted’ their opponents. Writing on the Great War Forum, ‘bieras’ gives vivid details of the scene in October 1917. Before the Great War, the Houthulst Forest covered over 4000 hectares but was reduced to fewer than a hundred hectares by the end of hostilities. [Link provided under Sources, but please regard it as having an associated Content Warning.]

On October 12th the 3rd Guards’ Brigade attacked enemy positions south of Houthulst Forest. This machine gun company sent 14 guns to assist. 6 were detailed for Barrage fire under Lt Cooke at [Wijzenroff?] 2 under 2nd Lieut Fallows at Pascal Farm, 3 under 2nd Lieut Hamilton went forward with the advancing Infantry while 3 guns under Lieut Wallis were in immediate reserve about Egypt House.

The Company were relieved in the Line by the 1st Guards Brigade Machine Gun Company on the night of Oct[ober] 14–15 Marched back to [word obscured] Camp in the Forest Area.

CASUALTIES

Killed 2/Lt W R HAMILTON 2 O[ther] R[anks]

Wounded 2/Lt R G SIMPSON (gassed) 25 O[ther] R[anks]

The silence on any events between the commencement of action early on 12 October and the night of the 14th/15th is deafening.

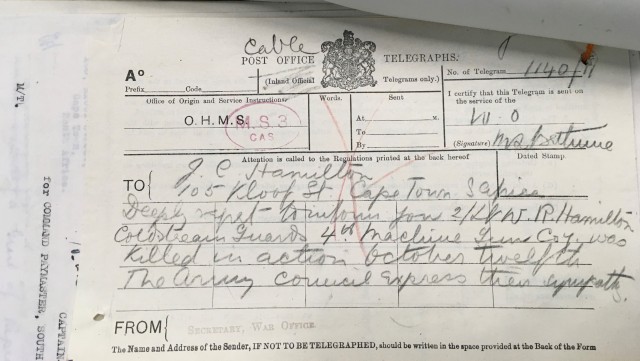

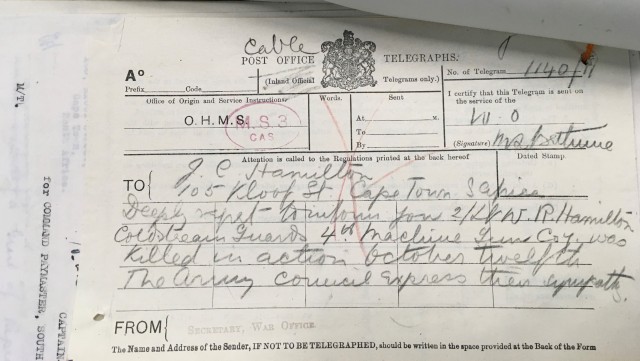

The Telegram

Despite the distance, and no doubt the confusion following the Disastrous Twelfth, it was not long before a telegram reached William’s father in Cape Town. It read:

[TO] J C Hamilton 105 Kloof St., Cape Town, South Africa

Deeply regret to inform you 2/Lt W R Hamilton Coldstream Guards 4th Machine Gun Coy was Killed in action October twelfth The Army Council express their sympathy.

Others who knew William, read the Casualty Lists with dismay. Ten days after William’s death, a clergyman, A W Woolverton, writing from Clevedon, Somerset, approached the Military Secretary in a letter enquiring into the identity of the soldier on the Telegraph’s list of officers killed.

27.x.17

Sir

I see by the D[aily] T[elegraph] list of officers killed, one, 2nd Lieut. W R Hamilton, C[oldstream] Guards. Can you inform me whether this is young Hamilton who came over from Cape Town? For I know him, & would like to write to his folk.

Yours truly,

Rev. A W Woolverton

There is a poignancy behind Arthur Wellesley Woolverton’s concern. While he and his wife, Rosa, had no children, he had a nephew, the son of his elder brother, Charles Nicholas Woolverton, who shared the name Arthur Wellesley Woolverton, and who was about the same age as William, who had died in France while serving in the 65/Field Ambulance, RAMC on 4 June 1917. His CWGC headstone has the memorable epitaph, Á Dieu.

A wee mystery

William’s service records contain several items of correspondence between his father and the Army. Two months after his son’s death, John Hamilton wrote to the War Secretary to inform him that he was his son’s sole executor. He included some requests:

I should be glad if you would kindly send all his valuables such as private letters and papers and any small articles of value. He was wearing a Diamond Ring which he has left to someone here and I should be glad if it was carefully sent out to me.

As William has no known grave, it is unlikely that the diamond ring was ever recovered. William’s will may reveal to whom it had been left.

The last years of John Crosbie Hamilton

William’s father, John, died in the Groote Schuur Hospital on 2 May 1944 and was buried in the Maitland Cemetery. He was 86, though the Death Notice, for which his widow, Agnes Mary Robotham, was the informant, gave his age as 76 years. Agnes was the daughter of a Welsh father and a Scottish mother. Born in the Cape, where her father was a police inspector, the family returned to England in the early 1890s. In 1924, Agnes returned to the Cape, following her mother and younger sisters who had re-emigrated in 1915. Agnes would not have known William.

Not immediately forgotten…

Perhaps over the months I have been unravelling the story behind William, and exploring the background of his associates, my search engine skills have improved. To my astonishment, soon after I had completed, as I thought, my post on William, I came across William Hamilton in Chapter 8 of A. St John Adcock’s For Remembrance: soldier poets who have fallen in the war, published in 1920. There is a Wikisource link to this chapter in my Sources list.

Adcock concludes his piece on William, by referring to, and then quoting, Henry Simpson’s If it should chance… followed by a final paragraph, on which I cannot improve.

If it should chance that I be cleansed and crowned

With sacrifice and agony and blood,

And reach the quiet haven of Death’s arms,

Nobly companioned of that brotherhood

Of common men who died and laughed the while,

And so made shine a flame that cannot die,

But flares a glorious beacon down the years—

If it should happen thus, some one may come

And, poring over dusty lists, may light

Upon my long-forgotten name and, musing,

May say a little sadly—even now

Almost forgetting why he should be sad—

May say, ‘And he died young,’ and then forget….

And because that must be true of the vast majority, one is the happier that these at least will be held longer in remembrance who could give words to their thoughts and emotions, which were the thoughts and emotions also of their comrades who died, and made no sign, and have put their hearts and minds into songs that are not so perishable as the singer.

Reflect with me, on the first of William’s War Sonnets, written in 1917, as he anticipates a future in which he suspects he will likely play no part, under a future government which will rattle on regardless of the consequences of repeating its historic mistakes.

War Sonnet I

The spoils of youth are shaken from the net:

The golden promise spilt, and in despite

Of nature’s well-laid plan, a nation’s might

Of intellect becomes a dull regret.

And ye, who lightly talk of England’s debt;

Who muddle into government and war,

Spilling the garnered ointment from the jar

The Past upon the Future’s altar set—

How shall ye meet this greater debt incurred

Of reasonable hope outraged, and how

Restore the sweetness to the People’s song:

Revive its pristine trust in those whose word

May yet precipitate a greater wrong

Than that whose bitterness we harvest now!

William Hamilton, Modern Poems, p.21

Points of interest?

Who died alongside William?

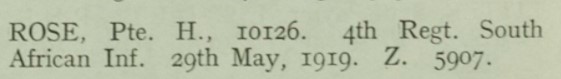

Reading the list of casualties in the 4/MGG Battalion’s War Diary for 12 October 1917, I felt keenly, as one does, the failure to identify the 27 injured from the lesser ranks. I searched for information on the two men of ‘other ranks’ who may have died alongside William, and who like him, have no known grave. I was only able to identify one of them, 775 Private Henry George Blyth (1894–1917) of the Machine Gun Guards, 4 B[attalion], who died on 12 October 1917 and who, like William, is commemorated on the Tyne Cot Memorial. The CWGC has no further information in its database, not even the names of his parents, nor his full name, nor the names of his wife and children. I will be writing a short piece on Henry and his link to Scotland—he married in Portobello—for my Passersby Remember blog.

Why the Coldstream Guards?

I frequently pondered over this, asking myself why William was so keen to enlist in the Coldstream Guards, as there seemed no family connection with that particular regiment. It was when I narrowed down his mother’s place of birth from England to Northumberland and finally to Crookham in the parish of Ford, that I found a clue. As I had begun to suspect, Crookham is close to Coldstream, and it may have been anecdotes her mother or her aunts shared with Jeanie, that she in turn shared with her son, William that inspired in him the ambition to serve in the Coldstream Guards. And if, during his childhood, he had been taken to England to see his mother’s birthplace, and seen the Guards on parade, that may have been what deeply impressed him.

While a new build, in 1932–1933, replaced the original Presbyterian church in Crookham, built in the 1730s, it is on the site of the old church, and is still following a similar tradition, but as a United Reformed Church. I was touched to discover that this church has recently been surrounded by a peace garden.

The SACS War Memorial

The SACS archivist responded swiftly to an enquiry, and was kind enough to send me a photo showing a section of the school’s memorial to pupils of the South African College School who perished while on active service. William’s name would have been between HAMBIDGE P G and HANSEN A D. I hope that the school’s English and History teachers and some of their pupils will be interested in reading and sharing William’s story., so that he is not forgotten by those who came after him.

It was not particularly unusual for South Africans to enlist in a British regiment. For example, elsewhere in this blog, you will find my post on Barney Rissik, grandson of Dr Gerrit Rissik, who served in the Rifle Brigade.

Bramblebank Mill

In 2002, Canmore (The National Record of Historic Environment) described the Bramblebank Mill as follows: A mid-19th century linen/jute mill utilising water from the River Ericht. The complex of buildings includes a three-storeyed & attic rubble-built mill with gabled slate roof, and a five-bay extension at its NW end. The mill was disused at the time of survey in 2002. Information from RCAHMS(MKO) 2002

Bramblebank Mill was gutted early in 2021, in an inferno thought to be the work of vandals. Thus was lost an industrial heritage site, spanning nearly 200 years. Some machinery survives, because, when the mill ceased production in 1903, the “cutting edge machinery” was moved to Westfield Mill, which was then being rebuilt.

Sources and documents

Adcock, A. St John, For remembrance: soldier poets who have fallen in the war, 1920.

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/For_remembrance:_soldier_poets_who_have_fallen_in_the_war/Chapter_8#273, accessed 11/12/2022.

Canmore, (National Record of the Historic Environment) ‘Blairgowrie, Rattray, Bramblebank Mill’, https://canmore.org.uk/site/112157/blairgowrie-rattray-bramblebank-mill, accessed 15/12/2022.

Cateran Ecomuseum, ‘Bramblebank Works’, https://cateranecomuseum.co.uk/site/bramblebank-mill/accessed 9/12/2022.

Elliott, C.C., ‘The History of the Cape Town Hospitals’, South African Medical Journal, Volume 21, Issue 16, p.377–380, August 1947, https://journals.co.za/doi/epdf/10.10520/AJA20785135_2562, accessed 11/12/2022.

General Register Office (GRO), Statutory Births 1863, ‘Jane Waugh’, Glendale (Northumberland), Vol. 10B, p.335.

Great War Forum, Map of Houthulst Forest, https://www.greatwarforum.org/topic/42257-houthulst-forest/, accessed 14/12/2022.

Great War Forum, ‘Houthulst Forest, October 1917, https://www.greatwarforum.org/topic/225845-houlthoulst-forest-october-1917/, accessed 16/12/2022. Look for contributions to this thread by Andrew Lucas aka ‘bierast’—there are also some photos that provide a strong impact. Also see entry for Andrew Lucas in this Source list.

Hamilton, W., Modern Poems, Oxford (Blackwell), 1917. The British Library has a copy of this book, but also provides access for registered users to an online digital copy.

Historic Environment Scotland (HES), ‘Bramblebank Mill, Rattray, Blairgowrie’, https://scotlandsplaces.gov.uk/record/hes/112157/blairgowrie-rattray-bramblebank-mill/rcahms, accessed 9/12/2022.

London, L[ucy], ‘Forgotten Poets of the First World War’, https://forgottenpoetsofww1.blogspot.com/p/list-of-forgotten-poets-of-first-world.html, most recent access 6/12/2022.

Lucas, A[ndrew] and Schmieschek, J[ürgen], For King and Kaiser: Scenes from Saxony’s War in Flanders, Pen and Sword, 2020. Warmly recommended. It’s a sequel to their earlier book ‘Fighting the Kaiser’s War’. It is always illuminating to understand what was happening in the opposite trenches.

Representative Poetry Online, ‘William Hamilton’, https://rpo.library.utoronto.ca/poets/hamilton-william, accessed 12/12/2022.

Royal Society of South Africa, Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa, Vol.34, Issue 1, ‘Hugh Adam Reyburn’, 1954, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00359195409518970, accessed 13/12/2022. This piece provides a brief overview of Reyburn’s career, evaluating and focusing on his character, interests, strengths and contribution to psychology.

The National Archives (TNA), WO 339/68909, Officers’ Records, ‘2 Lieutenant William Robert Hamilton, The Coldstream Guards’, 1914–1922.

TNA. WO 95/1206/1, ‘War Diary 4 Guards Battalion Machine Gun Corps, With Plans’, 1/3/1917–31/3/1918. Relevant images are on image 21/107 and 22/107. This War Diary is available to download from The National Archives.

Wikipedia, ‘Alfred Richard Orage’, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_Richard_Orage, accessed 12/12/2022.

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Passchendaele’, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Battle_of_Passchendaele, accessed 4/12/2022.

© Margaret Frood QG, 2022.